Day 25 of Noirvember: A Guest Post — Open Secret at the Turner Classic Film Festival

Now that the passes for the 2020 Turner Classic Movies Film Festival have gone on sale, this is a perfect time for another installment of my ongoing coverage of this year’s TCM event. But for today’s Noirvember post, I’m serving up a treat — a guest post from a first-rate writer and one of my favorite people, Aurora over at the Once Upon a Screen blog. Aurora is taking us inside one of the noirs that was screened at the 2019 film festival Open Secret (1948). Enjoy!

Now that the passes for the 2020 Turner Classic Movies Film Festival have gone on sale, this is a perfect time for another installment of my ongoing coverage of this year’s TCM event. But for today’s Noirvember post, I’m serving up a treat — a guest post from a first-rate writer and one of my favorite people, Aurora over at the Once Upon a Screen blog. Aurora is taking us inside one of the noirs that was screened at the 2019 film festival Open Secret (1948). Enjoy!

——————

A packed house was witness to a low-budget film noir at the Turner Classic Movie film festival earlier this year. It was probably the biggest crowd to ever watch John Reinhardt’s Open Secret (1948), as TCM host and Film Noir Foundation founder and president Eddie Muller noted during his introduction. “This is as B as B gets,” Muller said, which did nothing but pique the audience’s interest in what turned out to be an effective, down and dirty telling of an insidious presence in post-war, small-town America.

Hollywood had long resisted shining the light on Jewish stories despite the fact that the film industry was run primarily by Jews. It was after World War II that movies took a serious turn and, as Mark Harris describes in his brilliant 2015 book, Five Came Back, decided to grow up. Adult stories replete with realism were now in movie theaters and audiences responded with enthusiasm as did the Hollywood community, who gave Academy Award honors to stories of alcoholism, the difficulties of post-war reintegration, and the most taboo of subjects, anti-Semitism with Elia Kazan’s Gentleman’s Agreement (1947). Released that same year was Edward Dmytryk’s well-received, hard-hitting Crossfire, which was lauded by most critics for its superlative cast and frank spotlight on anti-Semitism, the same subject tackled in 1948 by John Reinhardt’s lesser-known, underrated Open Secret.

Hollywood had long resisted shining the light on Jewish stories despite the fact that the film industry was run primarily by Jews. It was after World War II that movies took a serious turn and, as Mark Harris describes in his brilliant 2015 book, Five Came Back, decided to grow up. Adult stories replete with realism were now in movie theaters and audiences responded with enthusiasm as did the Hollywood community, who gave Academy Award honors to stories of alcoholism, the difficulties of post-war reintegration, and the most taboo of subjects, anti-Semitism with Elia Kazan’s Gentleman’s Agreement (1947). Released that same year was Edward Dmytryk’s well-received, hard-hitting Crossfire, which was lauded by most critics for its superlative cast and frank spotlight on anti-Semitism, the same subject tackled in 1948 by John Reinhardt’s lesser-known, underrated Open Secret.

Sheldon Leonard was third-billed as a police detective.

John Reinhardt arrived in Hollywood just before the advent of sound to act, but made a name for himself by directing obscure Spanish-language films in Mexico for big studios like 20th Century Fox and Paramount in the early 1930s. Those productions were mostly comedies and musicals written by Reinhardt himself. After World War II, Reinhardt, who had worked for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) during the war under the command of John Ford, dealt in low-budget films of a much darker nature, such as The Guilty and For You I Die, both released in 1947. His most famous film is the cold war melodrama Sofia from 1948. Unfortunately, Reinhardt’s post-war filmography is short, as he died of a heart attack in 1953 at the age of 52. However, if Open Secret had been his only post-war film, Reinhardt should have been proud because it is a gutsy production. Open Secret follows in the footsteps of Crossfire, but manages a more oppressive atmosphere throughout.

The cast also includes Arthur O’Connell and Roman Bohnen.

Open Secret stars John Ireland and Jane Randolph as newlyweds Paul and Nancy Lester, who visit Paul’s Army buddy Ed Stevens on their honeymoon, only to find Ed missing when they arrive. As Paul investigates Ed’s whereabouts, the story slowly uncovers an ugly truth simmering along the streets of the unnamed city: bigots bent on ridding the neighborhood of Jews. As it turns out, Ed had proof of the crimes committed before he went missing – a roll of film that proves vital to getting to the root of the hatred. With the help of Det. Sgt. Mike Fontelli, played by Sheldon Leonard, Paul Lester bears witness to multi-generational hatred among the inhabitants of the town. Perhaps this is Open Secret’s harshest message, the children we see who have been taught to hate with such passion that their innocence is silenced. This depiction is starker than even the spousal abuse that seeps into the forefront of the 60-plus-minute film. Although the bad guys get what they deserve at the film’s conclusion, we know the seeds of prejudice have been planted in the shadows.

Ireland is a standout as the film’s hero.

John Ireland does a fine job as the hero of Open Secret, forging a path toward righteousness without fear of the dangers that run rampant in the town. Ireland, who was adept at heroic and villainous roles throughout his six-decades-long career, had made a name for himself in A Walk in the Sun (1945). He became the first Vancouver-born actor to be nominated for an Academy Award with his turn in Robert Rossen’s All the King’s Men (1949). Jane Randolph enjoyed a film career primarily in the 1940s, but is effective and believable as Ireland’s devoted new wife. Randolph’s film career may have been relatively short, but she appeared in several enduring classics such as Jacques Tourneur’s Cat People (1942), Anthony Mann’s T-Men (1947), and perennial favorite Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), directed by Charles T. Barton.

There are several other notable actors in Open Secret who turn in memorable performances. Sheldon Leonard, whose gruff voice and strong New York accent made him the perfect heavy, does a good job as the sympathetic detective. You’ll also catch glimpses of veteran character actor Arthur O’Connell, although his role here requires little more than barking orders as the “boss” of the gang committing hate crimes across the town. The most overtly hateful in the group, however, is Roy Locke, a hard-drinking man whose hobbies include murder and beating his wife. Locke is played memorably by Roman Bohnen with the role of Mrs. Locke delivered by character actor Ellen Lowe, who boasted several uncredited parts in big pictures like Citizen Kane during her career.

Also worthy of mention is George Styne who plays Harry Strauss, the Jewish owner of the photo store that plays prominently in the story. Styne was blacklisted during the McCarthy era, but bounced back to become a frequent television director, helming episodes of such notable series as The Odd Couple, Love American Style, and The Bob Newhart Show. Strauss is the character we most sympathize with in Open Secret as we witness how he is consistently harassed and his store vandalized in hopes he’d leave the neighborhood. Mr. Strauss remains steadfast, however, and we root for him as he becomes involved in resolving the mystery. There’s a particularly difficult scene to watch that takes place in a local bar where Jews are not served. The mocking of a man by people who think they are better, but whose faults are evident, is perhaps what makes Open Secret most relevant today. That and the disgust in their voices as they mention “foreigners.”

Also worthy of mention is George Styne who plays Harry Strauss, the Jewish owner of the photo store that plays prominently in the story. Styne was blacklisted during the McCarthy era, but bounced back to become a frequent television director, helming episodes of such notable series as The Odd Couple, Love American Style, and The Bob Newhart Show. Strauss is the character we most sympathize with in Open Secret as we witness how he is consistently harassed and his store vandalized in hopes he’d leave the neighborhood. Mr. Strauss remains steadfast, however, and we root for him as he becomes involved in resolving the mystery. There’s a particularly difficult scene to watch that takes place in a local bar where Jews are not served. The mocking of a man by people who think they are better, but whose faults are evident, is perhaps what makes Open Secret most relevant today. That and the disgust in their voices as they mention “foreigners.”

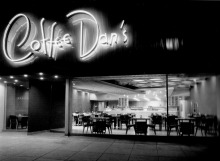

You will notice the lack of budget when you watch Open Secret. Eddie Muller joked that it was made for about $2,000. Or maybe he meant it. The sets are bare and the score is recycled, although none of that diminishes the power of the film’s message. In fact, Open Secret does a heck of a lot with very little, thanks in large part to the photography of George Robinson, whose work helps create the palpable dread in the film. Robinson was a prolific cinematographer who worked primarily at Universal, creating the look of many memorable films including several in that studio’s fabled horror canon.

Thought lost for years, Open Secret was restored by The UCLA Film & Television Archive, and festgoers had the pleasure of discovering the film with that print at the TCM festival. In that packed theater, the audience learned that Open Secret is a brave thriller that deserves to be seen.

——————–

My humble thanks to Aurora for a top-notch write-up on a fine film, which can be viewed on YouTube and other sites. Do yourself a favor and check out this film, pay a visit to Aurora’s Once Upon a Screen blog — and join me tomorrow for Day 26 of Noirvember!